Sex, love and robots: is this the end of intimacy?

The world is ending. The sports fields are empty, the science labs closed. No babies have been born for years. Cut to a split screen of human and robots kissing passionately. “They’re trapped!” says the narrator, voice like gravel. “Trapped in a soft, vice-like grip of robot lips.” Words slam against the screen, a warning. “Don’t. Date. Robots.”

Except Futurama’s 2001 episode “I Dated a Robot”, with its post-apocalyptic world of silvers and blues, wildly overestimated how long it would take before this fear became flesh. It’s November 2015, and in Malaysia, where humidity is at 89% and it is almost certainly still raining, David Levy, a founder of the second annual Congress on Love and Sex with Robots, is free to talk on the phone – he is less busy than planned. “I never expected to end up here,” he says. I hear a shrug.

The Congress on Love and Sex with Robots was meant to begin on 16 November, but was deemed illegaldays after Levy arrived from London. “There’s nothing scientific about sex and robots,” inspector-general of police Khalid Abu Bakar told a press conference, explaining why. “It is an offence to have anal sex in Malaysia [let alone sex with robots].”

“I think they thought people would be having sex with robots or some strange thing like that,” Levy’s co-founder Adrian David Cheok said afterwards, explaining that they had planned a series of academic talks about humanoid robotics. But some strange thing like that, some strange thing like a human having sex with a robot, is what Levy, Cheok and others are predicting is almost our reality. They have seen the future of sex, they say, and it is teledildonic.

Teledildonic. The word rolls around the mouth like a Werther’s Original. While there are a variety of romantic tech-sex developments appearing weekly – from the ocean of Oculus Riftpossibilities to an invisible boyfriend who lives on your phone, each new development rich as a Miranda Julystory but as doom-laden as one of Margaret Atwood’s – it’s teledildonics that are exciting not just the porn industry, but scientists too. Long hyped as the new wave in erotic technology, these are smart sex toys connected to the internet. And while they started life as vibrators that could be operated remotely, today the term has expanded to loosely include the new generation of robotic sex dolls.

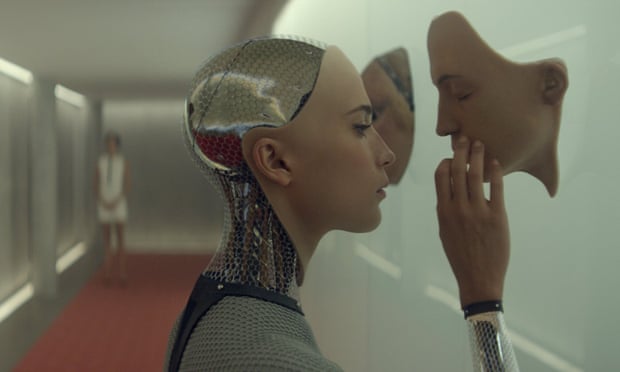

Cultural analyst Sherry Turkle warns we’re rapidly approaching a point where: “We may actually prefer the kinship of machines to relationships with real people and animals.” Certainly we have long had a fascination with these half-women, from The Bionic Woman in the 1970s to Her in 2013, where Joaquin Phoenix fell in love with his computer’s operating system. This year, Ex Machina’s Ava seduced, killed and killed again. In 2007 Ryan Gosling starred opposite a “RealDoll”, Bianca, in the indie romance Lars and the Real Girl. The film ends with him gently drowning her in a lake.

A recent study by Stanford University says people may experience feelings of intimacy towards technology because “our brains aren’t necessarily hardwired for life in the 21st century”. Hence, perhaps, the speed at which relationships with robots are becoming a reality.

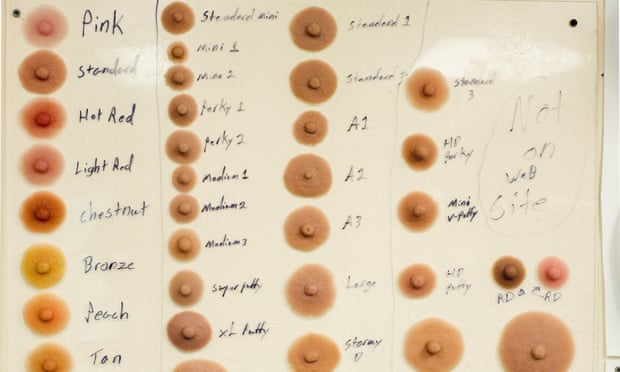

Today the RealDoll team, infamous now for its lifelike sex dolls (of which they claim to have sold more than 5,000), is extending its range to develop an artificial intelligence system capable both of following commands and talking back to its user. A Realbotix head (reports the New York Times) which can be attached to the existing RealDoll body will cost around $10,000, and will be available in 2017. In a piece entitled “Is This the Dawn of the Sexbots?”, the company’s owner David Mills explained the appeal of these warm-to- the-touch dolls, telling Vanity Fair he loves women but “doesn’t really like to be around people”.

“Women have enjoyed sex toys for 50 years,” he said (after introducing his first model, which arrived at his home in what looks like a customised coffin, head not yet attached), “but men are still stigmatised. We have to correct that. I want to be the Rosa Parks of sex dolls. Men are not going to sit in the back of the bus any more.”

The people leading us into the future of sex had other lives before (RealDoll’s Mills, for instance, is best known for the book Atheist Universe, which Richard Dawkins cites as “admirable work”). David Levy is a British international master of chess. With his white hair and a sharp eyebrow, he has the look of a cynical Einstein. It was chess that led Levy to computing, consulting in the late 1970s on the development of a chess module for home computers. In 1997, and again in 2009, he won the coveted Loebner prize, which awards the programme that is best able to simulate human communication.

“What do you do when you’re not doing the Loebner prize?” asked Judge 3 to Levy’s chatbot, Do-Much-More (the offspring of his first winner Do-A-Lot). “Oh, I do much more than I intended to do at first. I got more interested in the job as I went along.” Judge 3: “Is that difficult?” Do-Much-More: “No, it isn’t at all difficult. It is as peaceful as a platypus playing with a potato pudding.”

In 2007 Levy published Love and Sex with Robots, a book that one USA Todaycritic found “troublingly arousing”. Just as same-sex love and marriage have finally been embraced by society, he argued, so will sex with robots. “Love with robots will be as normal as love with other humans,” he wrote. The dream is, as one would expect, utopian. Prostitution will become obsolete. Artificial intelligence will be the answer to many of the world’s problems with intimacy. “The number of sexual acts and lovemaking positions commonly practised between humans will be extended, as robots teach us more than is in all of the world’s published sex manuals combined.”

Levy predicted “a huge demand from people who have a void in their lives because they have no one to love, and no one who loves them. The world will be a much happier place because all those people who are now miserable will suddenly have someone. I think that will be a terrific service to mankind.”

Unless… Unless… One chilly night in February I was chilled further by The Nether by American playwright Jennifer Haley. The story is set in a dystopian future in which people, so disillusioned by real life, decide to abandon it altogether, “crossing over” to spend all their time online in virtual worlds such as The Hideaway. Here, protecting their anonymity by living as avatars, they are able to do whatever they want. They rape children. The online world is sunlit and quaint, with a jolly host called Papa, who, when they enter, offers his guests a little girl. After they’ve had sex with her, they are invited to slay her with an axe. There are “no consequences here”, assures Papa.

And in this play is one of the questions that arises when we stare into the near-future of sex, with its machines and its promises, its employment of the technology used for shoot-’em-up games now reinvented for fucking. Porn actor Ela Darling, when asked by Vice in a discussion about tech and sex: “What would you do if someone fully scanned you and could do whatever they wanted with you?” answered: “That’s probably the future. And that’s OK with me.” Is it a robot’s role to do the things that humans can’t, or won’t? Will they be the solution not just to the problem Levy discusses, of loneliness, but to the problem of people whose desires are illegal? And then what does this mean for the rest of us?

Robots are evolving fast. They were invented in Bristol in 1949 by William Grey Walter, who was investigating how the brain works. It is fitting then, that down a wooded slope on the University of the West of England campus, the Bristol Robotics Laboratory is today considered a world leader in its field. The lab covers an area of 3,500m2, its vast yellow-lit space divided into glass sections littered with hard drives and disembodied prosthetic limbs. In the centre is a house. This is their “assisted living” smart home, where researchers are testing systems that could help people with dementia and limited mobility. By the sofa is a “sociobot” that can respond to facial expressions. The most human-looking of the systems, over by the dining table, is a robot called Molly. She has a tablet in place of a chest, for displaying photographs, and “She’ll say, for instance,” my guide explains: “‘Do you remember Paris?’” In that echoing space I found myself suddenly breathless.

When David Levy was 10 he visited Madame Tussauds waxworks museum with his aunt. “I saw someone,” he said, “and it didn’t dawn on me for a few seconds that that person was a waxwork. It had a profound effect on me – that not everything is as it seems, and that simulations can be very convincing.”

Levy has rarely left the air-conditioned confines of his lab since he arrived in Malaysia. There are no windows. The door leads on to the forecourt of a small shopping mall, and next door, looming yellowly beside the river that marks the border with Singapore, is Legoland. On Google Maps it looks as though a giant child has discarded a toy on her way in for tea. In his lab Levy is working on the new Do-Much-More, a chatbot that, he says, after two weeks is already better than last year’s Loebner winner. “When you have a robot around the home,” he tells me, “whether for cooking or for sex, wouldn’t it be nice to be able to have a chat with it?”

Levy has very little time for jokes. Or, it turns out, for philosophy. “Are humans machines?” I ask him. He tells me he’s learned not to try to answer philosophical questions. Ethics, however, he’s interested in. “People ask: is it cheating? Only if women using vibrators are cheating. Will sex workers be put out of business? It’s possible.” What about bigger issues though – what about sex and empathy? And: can a robot consent? “When AI advances, robots will exhibit empathy. People will feel towards them as they do towards animals.”

He pauses: “Look. One has to accept that sexual mores advance with time, and morality with it. If you had said a hundred years ago that, today, men would marry men and women women, everyone would have laughed. Nothing can be ruled out.” Nothing? “You think that’s scary? Millions of scary things rely on technological advances. Toy drones, for example. That you can buy on the high street and attach anthrax to, and kill hundreds of people. This, this I find frightening.” It took some time (we continued our discussions on email) before Levy was prepared to answer a question about the thing that had been troubling me – if robots are his solution for men who can’t have relationships, does he think they’re also the ethical choice, say, for a man who wants a relationship with a child?

He was reluctant to discuss this, pointing me to a keynote talk he did in Kathmandu called “When Robots do Wrong”. Which was fascinating, but didn’t answer my question. Eventually he responds, his email a sigh. “My own view is that robots will eventually be programmed with some psychoanalytical knowledge so they can attempt to treat paedophiles,” he said. “Of course that won’t work sometimes, but in those cases it would be better for the paedophiles to use robots as their sexual outlets than to use human children.”

However evolved they become, robots will always be distinguishable from humans. They call it the “uncanny valley” – the point at which humans become uneasy at a robot’s humanness. So, even as the technology evolves, scientists will ensure there will always be something. Not a glitch, necessarily, not a ding, but a something. “And because of that, robots will never replace humans. They’ll simply become an extension of our lives.” Levy’s main thesis is that the advent of sex robots will help the lonely. The people who find it impossible to form relationships. “If that were me, I’d rather have sex with a robot,” he says, “than no sex at all.” Robot sex, it’s implied, could save humanity. His wife, he tells me, is sceptical about the idea.

So is ANTHROPOLOGIST Kathleen Richardson. She says: “Levy is wrong.” Richardson is a senior research fellow in the ethics of robotics at De Montfort University and director of the Campaign Against Sex Robots. “David Levy is taking people’s insecurities and offering a solution that doesn’t exist,” she explains. “Paedophiles, rapists, people who can’t make human connections – they need therapy, not dolls.”

She perches on the edge of an armchair and explains the recent history of robots. Over the past 15 years, the purpose of robots developed for domestic use quietly changed. In South Korea they have set a goal for every home in the country to have domestic robots by 2020. But will they really be tools to help around the house, or will their main appeal be as a companion?

“This move,” towards socialised robots, “is happening in hyper-capitalist societies driven by neo-liberal ideas.” Where people, she says, are becoming distant from each other; where in warm living rooms families sit together but apart, each concentrating on individual screens. It’s a direct path, she believes, from the way we communicate through machines, from social networking, to robots. And this, she says, is dangerous.

Richardson looks at how we attribute sociability to objects. She showed me a silent animation from 1944, in which two triangles and a circle move around a diagram of a house. To me, it was clear both that this was a tragic love story, and also that I was being moved by anthropomorphised lines. “A robot is not just a developed vibrator,” she laughs, the sort of laugh that does not necessarily follow a joke. As the sex trade with machines grows, and these objects take on increasingly humanoid forms, Richardson will be asking: “What does this mean? And is it harmful?”

As I explore the Bristol Robotics Laboratory, I realise that each glass-partitioned wall surrounds another ethical dilemma. The drones, so helpful when monitoring climate change. Tiny swarming “kilobots”, inspired by ants, modelling future ideas for cancer treatment. The too-realistic human head, with its soft skin and unfinished skull. Here there is a feeling of scholarly possibility, fuelled by earringed men, large coffee cups. In one cubicle, knee-height Nao robots feature in an experiment in which Professor Alan Winfield,part of a British Standards Institute working group on robot ethics, asks: “Can we teach a robot to be good? But when the research goes public and outgrows this hangar-sized lab, each robot will inevitably be reshaped depending on who acquires it.

An apology. I thought this article would be a bit of fun, honestly. A romp through the kinky silliness that’ll be marketed at our grown grandchildren, their poor glazed eyes consensually replaced with tiny computers. A funny toy, a cheeky app maybe. A widower watching TV with his unseeing doll, more of a carer than a wife. And then I went and spoiled it all by asking questions. Assuming technology doesn’t start rolling backwards, people will be having sex with robots in the next five years. Before RealDolls manages to refine and sell its robots, with their lubricated mouths and their custom eye colours, there are entrepreneurs who are competing right now to market their own versions first.

While buyers of Pepper – a robot engineered to be emotionally responsive to humans – have signed user contracts promising they won’t use it for “acts for the purpose of sexual or indecent behaviour”, sex doll company True Companion is developing a robot that will be “always turned on and ready to play”. Roxxxy is due to go on sale later this year – in May they’d had 4,000 pre-orders at £635 each. “She doesn’t vacuum or cook,” says Douglas Hines, Roxxxy’s creator, “but she does almost everything else.”

When I heard about Richardson’s Campaign Against Sex Robots, I sniggered. It conjures up every Giles Coren-esque description of the most furious feminist imaginable, charging into the future with a mallet and a frown. Richardson admits it’s not… unfunny. But then she shrugs. What else is she going to call it?

Richardson and Levy stand on opposite sides of a busy road, watching technology speed past towards a clouded horizon. If the future of sex (as all arrows seem to point) is in robotics, then Richardson is right: it requires a thoughtful discussion about the ethics of gender and sex. But while she identifies the relationships that appear to be emerging as modelled on sex work – the robot as passive, bought, female; the man as emotion-free and sex-starved – surely rather than calling for a ban on them, to forlornly try stalling technology, the pressure should be to change the narrative. To use this new market to explore the questions we have about sex, about intimacy, about gender.

I agree with Kathleen Richardson on many things, especially that robots should not be the prescription for those who struggle with the otherness of people (something she said in the context of relationships with robots – that humans become human through interacting with other humans – I’ve thought about most days since we met). But until the internet becomes the Nether, until it becomes so immersive that our grasp on reality becomes slippery, I think it’s a mistake to fear it, and to fear them. Because this is what we know: the sexbots are coming.

Comments

Post a Comment